By Genevieve Azelama

Long before the advent of Europeans, the rivers and the lands of the Ashanti Kingdom flowed with gold, an African empire which lasted from the 17th to the 19th century. Here, gold did far more than adorn; it governed, inspired, and empowered.

For centuries, the Ashanti kings known as Asantehene mastered the art of transforming the earth’s glimmering bounty into the bedrock of an extraordinary economic and Cultural Revolution that turned civilization. Gold wasn’t just a symbol of wealth; it was a tool of diplomacy, a catalyst for art, a source of military might, and an emblem of African excellence.

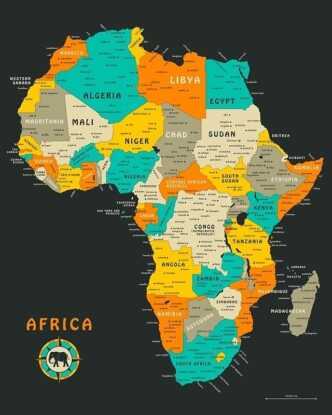

Today, Ghana, or the Gold Coast, stands atop rich mineral reserves and landscapes. We take a look at exploring in understanding the brilliance of the Ashanti pre-colonial gold economy, an African model of innovation, sustainability, and statecraft.

In Ashanti thought, gold was more than metal or jewelry; it was a way of life.

Their lands, fruits were seams of gold which led to the birth, an economy where gold dust served as currency of the land. The Golden Stool stood at the heart of this world of glimmer and shine; it was a sacred symbol of the soul of the Ashanti nation. All kings who ruled the Ashanti kingdom swore allegiance to it; it was an anchor of cultural, spiritual, and moral value.

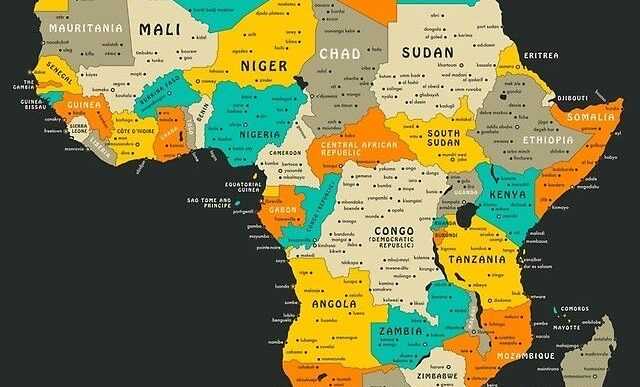

Under the reign of mighty leaders like Osei Tutu and Osei Bonsu, gold mining became a state enterprise. Ashanti rulers exercised centralized control over production and empowered local communities to participate in panning and deep-shaft mining. Gold mining became an empire-wide enterprise practiced from the Wassaw and Aowin goldfields. Gold was harvested in the thousands by the Ashanti people.

The Ashanti people were geniuses of innovation in their right way before mordent technology and practices they came up with a system that demonstrated their remarkable technival skill and ingenuity by Utilizing lost-wax casting, artisans created some of the most intricate and brilliant gold jewelry, regalia, cultural and traditional artworks and ceremonial objects the world has ever seen.

Yet this was just another marvel in comparison to their most sophisticated creation, their currency system. Standardized gold weights, small brass figurines shaped in geometric forms or symbols of Akan proverbs, ensured trade fairness. Thereby creating a currency value metric system far before what is used in our present day, Gold dust was meticulously weighed on scales, its flow lubricating both local markets and trans-Saharan trade routes, as Ashanti gold through trade found its way throughout the globe.

The gold economy helped with the establishment of ingenious, well-maintained roads radiating from Kumasi; gold connected the Ashanti to a vast trading world. From Morocco’s souks to the shores of Europe, Ashanti gold funded the import of textiles, salt, firearms, and luxury goods, transforming the kingdom into a hub of commercial vitality, setting up the Ashanti kingdom as a stunning example of a well-functioning and stable economy.

The economy of the ancient Ashanti people prioritized a system where wealth redistribution was standardized, unlike extractive models we see in present times, where many are impoverished for the benefit of a few. Chiefs received portions of gold revenue, mandated for the use of empowering local governance structures. Upon a king’s death, intricate inheritance laws ensured wealth flowed back to families and the state.

This circulation of gold sponsored festivals where the culture and glory of the Ashanti empire was on full display, funded expansive armies, sustained developed architecture and industries, provided and grew the Ashanti people, and sustained public works. The annual Akwasidae festival, for instance, showcased the opulence and spiritual depth of Ashanti wealth, with chiefs donning layers of gold jewelry and processions exalting the Golden Stool.

Art, culture, and heritage were all woven in golden threads. The Akan gold weights themselves became bearers of oral history and wisdom, their symbols teaching values and holding cultural and historical value and reverence across generations.

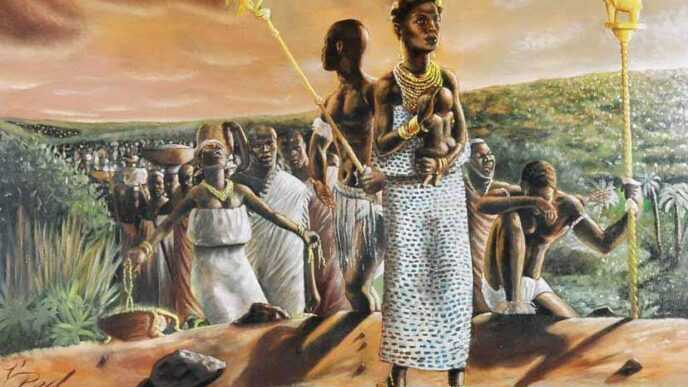

At the end of life on earth and the life after for the Ashanti people spoke. Royals were buried with gold ornaments, which served as an affirmation of life’s transience and the immortality of the Ashanti spirit. Women were central to this economy; they were the traders in the marketplace, the guardians of the gold weights, controlling most of the gold economy in reverence to the Ashanti queens, Asantehemaa, who held major influence in political and economic decision-making.

Even after British Intrusion and the violent dismantling of the Ashanti gold economy and the takeover of Ashanti mines and minted coins by the late 19th century, the cultural economy of the gold economy persevered. Today, the Ghanaian cedi draws its name from the Akan word for “cowry,” once traded alongside gold dust. The Ashanti Region remains a symbol of Ghana’s mineral wealth and cultural strength.

In a world today where the brilliance and ingenuity of African economic systems and practices are often underplayed or cast aside, the Ashanti gold economy stands tall as a model of sustainable wealth creation, decentralized innovation, and cultural resilience.

It stands as a reminder that the culture and tradition extended far beyond what we wore or what we ate, but also consisted of intricate and exemplary institutions across industries.

African innovation has always glistened in markets, in artistry, and leadership. And it still shines today.