By Genevieve Azelama

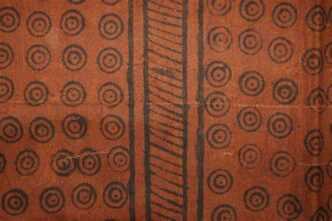

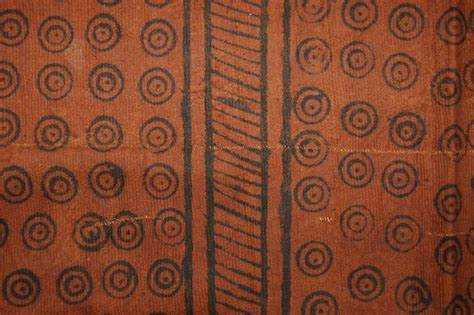

The Barkcloth of Southern Uganda is a soft and supple material that carries strength and resilience not only in its production but also in its significance and historical journey. The Barkloth might even predate woven material is known as olubugo and is gotten from a species of Fig tree, specifically Ficus natalensis, known as the Mutuba tree by the Ugandan people.It is no ordinary tree, as the people of Uganda have utilized this tree in making a noteworthy and sustainable textile.

A highly significant use of the Barkcloth is its use in swaddling the dead. The Mutuba tree itself is highly symbolic. In Buganda, the Mutuba is a marker of male strength, authority, and land ownership. It grows fast, regenerates quickly, and is fiercely rooted. It is, in every way, a metaphor for the endurance of a people.

From the inner bark of this tree comes the olubugo is created by boiling the tree bark to make it soft and malleable during production, then it is pounded with a great amount of strength for several hours, next it is sun dried, which gives it its signature rusty colour. In efforts to preserve and sustain the Mutuba tree, the bark is covered in banana leaves until the next harvest.

The origins of this textile marvel can be traced back to the oral legends of the Baganda people. Originally, the Olubugo was reserved for royalty as Kings and Queens were adorned with them, and spiritual leaders used them in rituals to communicate with their ancestors. However by the 18th century his production and user of the barkcloth was institutionalized during the reign of King Ssemakookiro, he transformed the barkcloth into an economic and cultural mainstay by mandating mass production by all his subjects’ turning the barkcloth into a prized commodity held economic value as it was used in trade, land tax, gifts and even diplomacy.

The British colonialists touched down on Ugandan soil, great efforts were made to halt the barkcloth from halting its production, to felling the Mutuba trees, and even condemning it through the guise of religion as satanic. The colonialists made efforts to offer European textiles as a substitute, forcing farmers into cotton farming. But barkcloth refused to disappear. It bided its time like a seed beneath the soil.

Instead, the Barkcloth became a symbol of resilience to the British colonies, In 1953, when the British exiled King Muteesa II to England, the people responded not with guns, but by adorning themselves in Barkcloth re-emerged as a visible symbol of loyalty to the monarchy of King Muteesa and quiet defiance against colonial domination. Thus reclaiming their cultural identity and heritage in resilient protest.

The production process of the barkcloth remains a sacred process carried out by skilled artisans who are inheritors of centuries of knowledge and skill.

In 2005, UNESCO designated it as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and today the Barkcloth is being revived by artists and artisans, who are reimagining its potential from fashion runways in Kampala and Berlin to sustainable textiles in experimental design labs. Uganda’s barkcloth serves as a tactile reminder that identity is not produced in a time of quick fashion and disappearing histories; rather, it is gathered, kept, and transmitted like a sacred flame. Quiet, steady, and indestructible, it is a heritage sewn with thunder rather than thread.